The address was written in a familiar scrawl, my full given name, apartment number, and in huge, all caps: BROOKLYN, NEW YORK. A care package from Tennessee, from Hoot. I attempted to slice open the relentlessly taped box with my true love’s ZZ Top keychain. Did I stop carrying my knife when I moved here? A subtle shedding for a more citified respectability? Where is my knife?

Old Commercial Appeal newspapers wadded up with intensity, with care, protecting fragile buried treasures within. As I dug into the box, my hands felt the quilted glass ridges of a mason jar first. The sun refracted through the spicy sweet red yellow thickness, the small hunks of peppers reminding me of amber around a mosquito. Pepper Jelly. I discovered other jars less translucent, a deep space darkness within. Blackberry Jam. Light doesn’t get through the airtight bricks of brown craggy chunks. My inheritance: Pecans. Underneath the jars of jelly, pecans, and I almost forgot, pepper sauce, too, one golden boot lay sideways.

To hold such an artifact in my hands in New York was dizzying. Nothing inanimate about that object. It danced in a necromantic chaos— carrying me through the veils of time, memory, and missing. A portal to The Great Boot Scoot Boogie in the Sky, dead cowboys taking me by the hand.

I was back in Tennessee standing before a ragged shrine built on the ruins of you in the old house. The Golden Boot filled with plastic flowers, glittering like the last of the sun on the creek behind the coop where the peacocks slept.

Just out of sight a grainy picture hung next to the huge wooden snowshoes from a far away hameaux. An at least 8x10 photo of bad quality, but framed—this is information. Your drag name that day was Françoise. In your dress and your wig you sat on the lap of man with lust in his eyes. Your son watched from the front row of seats in the assembly room at the school fundraiser giggling at the oranges you stuffed in your bra.

Frenchy, my grandfather, figured he didn’t need much English to give a fresh cut. The GI BIll and the white mobility it subsidized made it possible for him to open up a little barber shop just outside the Navy base in Millington. Twenty minutes from the shop and deeper into the country he set up his own little Acadiana on top of a ridge in Drummonds, TN, an hour or so north of Memphis. It was no Madawaska but I suppose hameaux is where the peacocks are.

Frenchy was a dandy. A bright-eyed, gorgeous cowboy with tight jeans, a thick accent, a signature scent of musk, ivory soap, barbicide, and grease. A stack of bandanas at the ready. He rubbed the necks of the soldiers in his chair before a fresh fade was served. He went dancing with my Granny every Saturday night. I loved his masculinity. I loved the flamboyant cowboy magic he brought to every function. I loved his love.

I’ve worn his boots. I’ve worn his bandanas. And, I’ve caught the eye of many through the glimmer of the pearl snaps on the shirts of his that I took with me after he died.

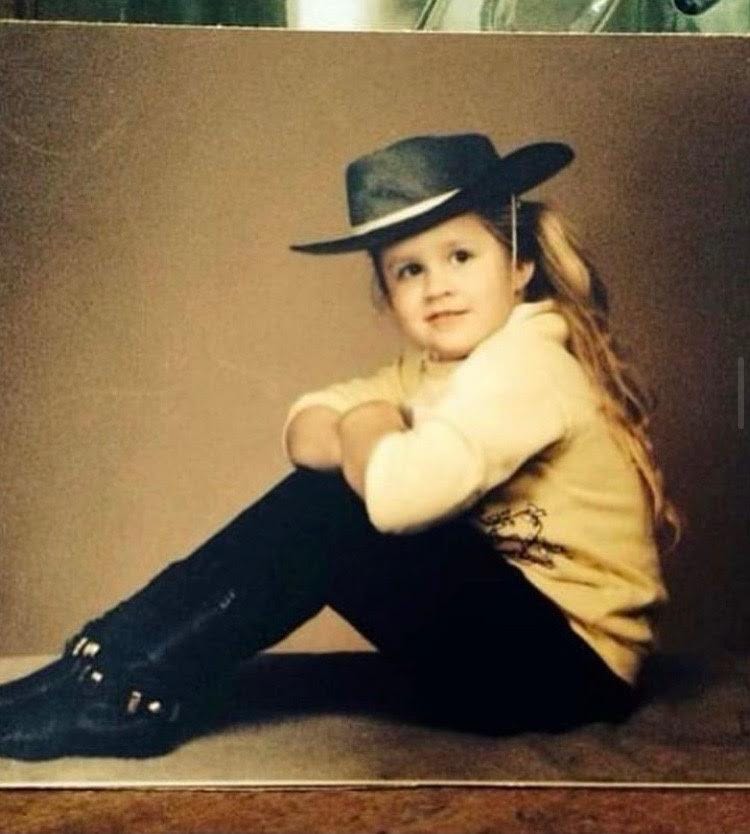

Long after the days that my mom joked about hiding the scissors, I’ve had the pleasure of a fresh cut. Those summer fades sure do let the breezes in, and the buzz of the electric shaver offers a trance I enjoy. Of course, there were signs early on that this was my path, the path of the queer cowboy.

I felt a deep sadness when Frenchy told me he tried to burn off all his tattoos with a hot knife and some weird chemicals. Of course, he told me this when I started getting my own tattoos. Cautionary tales became more frequent as I became more obviously queer. Because Frenchy was queer, too. Do you see?

When the untreated syphilis started eating up his brain with an insatiable appetite, he painted his boots gold. There were other events in his descent into the realm of the memoryless that I could tell you about but I’d rather not.

Trash burning in rusted out oil drums, shotgun shells strewn alongside fish guts, snakes hiding in barrels collecting rainwater. When I was young I didn’t always feel the most at ease out at my grandparents’ house. The smell of secrets and cow shit, mean dogs, and even meaner country cousins who taught me how to survive a drowning among other terrors. A generally accepted culture of misogyny and pageants of martial masculinity that I was given day passes to on occasion; a commitment to a belligerent whiteness by some that made no sense to me. There were also delights for a young queer heathen like me out there in the southern wilds–driving the four wheeler, fishing, digging up sweet potatoes for granny, a dirty fridge out back filled with Juicy Fruit, Cokes, Natty Lights, styrofoam cups overflowing with nightcrawlers, medicine for the cows. I’d sneak away to the creek and dig for fossils and pretty rocks that I would study later at my little desk in the apartment I lived in with my mom in Memphis.

Down there in those creek bottoms I found sanctuary, shelter in the broad day light. But, I was still in earshot of the dinner bell. What a thrilling call to action a dinner bell can be! For whom that clang tolls. I gathered my fieldwork and took a breath. Sunday supper was imminent. I was running up that hill and through the pastures, too, sprinting but cautious. Cottonmouths and Copperheads were everywhere.

Roast, butterbeans, ployes. Have you ever had Maine salad? Tomatoes from the garden salted and cut rough, raw white onion, lots of black pepper, ripped iceberg, and spoonfuls of Blue Plate Mayo all mixed up. A perfect, no frills punch to the buds alongside the rich meat and ployes, pronounced plooooeees if you were at my Granny’s table.

Have you ever had a ploye? Buckwheat flour, white flour, baking powder, cold water, boiling water, salt. Cast iron skillet greased and hot. The bastard child of a crepe and a pancake is born. The batter pops when kissed by the skillet's heat, leaving a landscape of little holes, future tidelands of butter. Granny cooked and Frenchy made plates, spooning out mountains of meat and beans and buttering everyone’s ployes, pulling them out, one by one, from a stack wrapped in a clean kitchen towel to hold their warmth. A bouquet of peacock feathers, the centerpiece of our crowded table. Just another Sunday supper out in the queer country.

I’m really glad I found your Substack. Your writing is amazing. Thank you for this on a rainy PNW Sunday.